uncan Tonatiuh is an author and illustrator, whose award-winning books have brought the themes of the Latino experience, immigration, social justice and more to the lives of children through a style inspired by Pre-Columbian art. We caught up with Duncan to talk about his work and the state of the children’s publishing industry.

For those who don’t know you, can you introduce yourself and your work?

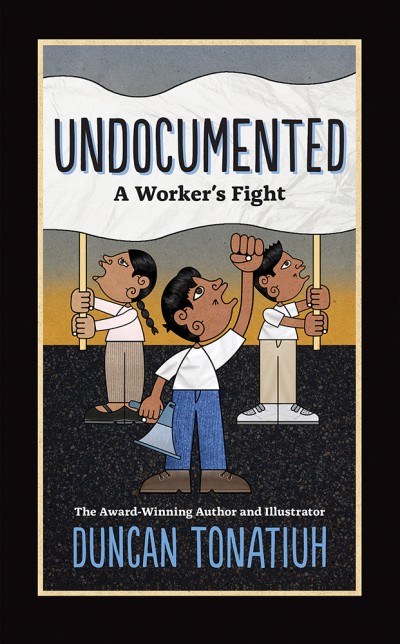

My name is Duncan Tonatiuh (toh-na-tee-YOU). I am the author-illustrator of Dear Primo, Diego Rivera: His World and Ours, Pancho Rabbit and the Coyote, Separate Is Never Equal, Funny Bones, Danza!, and The Princess and the Warrior. I am the illustrator of Esquivel! and Salsa: A Cooking Poem. All my books so far have been picture books for children. My upcoming book is called Undocumented: A Worker’s Fight. It is for adults. Some of my titles are fiction and some are non-fiction. They are all pretty different from each other, but the common theme among them is that they deal with Mexican culture in some way.

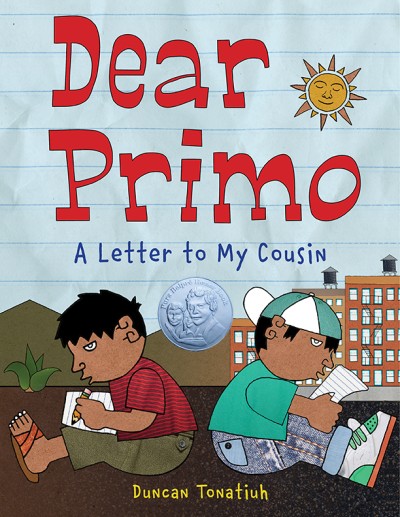

Is it true that you were contracted by Abrams Books straight out of college to publish your first book, Dear Primo? What did that feel like?

Yes. I attended Parsons School of Design in New York City as an undergraduate. A professor there really liked the illustrations I was creating for my senior thesis. She asked me if she could show my work to a children’s book editor at Abrams she was friends with. I said of course. The editor liked my work and I met with him at his office, which happened to be about 5 blocks from where I went to school. He told me that if he received a manuscript that suited my illustration style he would get in touch with me. Picture books are usually written by one person and illustrated by another one. I told him I liked writing too, and that I was taking writing courses at Eugene Lang College, Parsons’s sister school. He gave me his email and told me a few basic things about picture books, like the fact that they are usually thirty-two pages long and that it is a good idea to have the main character be a child or an animal so that young readers can identify with him.

Yes. I attended Parsons School of Design in New York City as an undergraduate. A professor there really liked the illustrations I was creating for my senior thesis. She asked me if she could show my work to a children’s book editor at Abrams she was friends with. I said of course. The editor liked my work and I met with him at his office, which happened to be about 5 blocks from where I went to school. He told me that if he received a manuscript that suited my illustration style he would get in touch with me. Picture books are usually written by one person and illustrated by another one. I told him I liked writing too, and that I was taking writing courses at Eugene Lang College, Parsons’s sister school. He gave me his email and told me a few basic things about picture books, like the fact that they are usually thirty-two pages long and that it is a good idea to have the main character be a child or an animal so that young readers can identify with him.

Sometime later, while I was still finishing my senior thesis, I had an idea for a picture book about two cousins —one that lives in a rural community in Mexico and one that lives in an urban center in the U.S.—who send letters to each other. I wrote the story and sent it to the editor. He liked the concept a lot and after many revisions it became my first published book, Dear Primo: A Letter to My Cousin. It was my first job out of college. I feel very lucky that the opportunity to do children’s books presented itself to me. Although my books are for young readers, I am able to make work about issues that I find important like art, history and social justice.

Tell us about the Mixtec culture that informs your work.

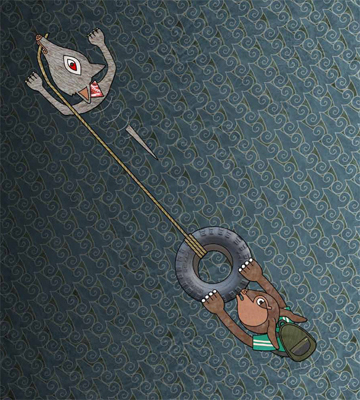

When I lived in New York, I sometimes volunteered at a worker’s center called NMASS (National Mobilization Against Sweat Shops). There I became friends with someone that was Mixtec. Mixtecs are an indigenous group from the south of Mexico and there is a large Mixtec community in New York. I was not aware of that, and for my senior thesis I thought it would be interesting to make a comic book about my friend’s journey from his small village in Mexico to his life as a busboy and community organizer in New York.

One of the first things I did when I began working on the project was go to my university’s library to look up Mixtec artwork. In books, I found reproductions of ancient Mixtec codex. I was familiar with Pre-Columbian art. I grew up in Mexico and I remember seeing Pre-Columbian art in the cover of school text books. But I didn’t pay much attention to those drawings when I was young. When I was a kid the things that made me want to draw were comics and anime. That day, though, when I saw the codex, I was drawn in by their geometry, flatness, and repetition of color. I decided that for my thesis I would make a modern day codex of my friends journey. I’ve been drawing in that style since.

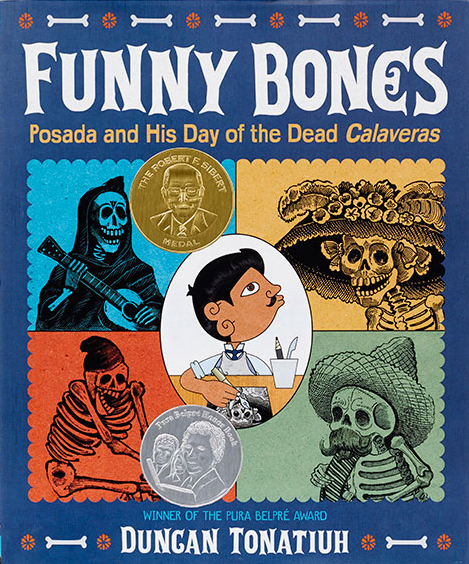

As you might have guessed, our favorite book of yours is Funny Bones, about the legendary printer Posada, whose calaveras have seen a bit of a resurgence since the movie Coco became a smash hit. What piqued your interest in him?

It is very common to see reproductions of Posada’s work during the Day of the Dead in both Mexico and the U.S. In San Miguel de Allende, where I grew up, there is even a Catrina parade where people dress up like fancy skeletons and parade down the street. It is a parade inspired by Posada’s print of a calavera with a fancy hat.

It is very common to see reproductions of Posada’s work during the Day of the Dead in both Mexico and the U.S. In San Miguel de Allende, where I grew up, there is even a Catrina parade where people dress up like fancy skeletons and parade down the street. It is a parade inspired by Posada’s print of a calavera with a fancy hat.

But although Posada’s artwork is well known, Posada himself is not. I made Funny Bones so that I could learn more about the man behind the calaveras. One thing that I really like about Posada’s artwork is that it feels timeless and that it makes me ask questions. Why did he draw that skeleton with a fancy hat? Is he trying to tell us that you can wear elegant clothes on the outside, but that on the inside we are all the same? That we are all calaveras?

One of the few holidays we close for is May Day, or International Workers’ Day, celebrated on May 1. For many years now, a strong focus of May Day has been the immigrants that work hard to keep this country afloat but who are so often exploited and scapegoated. How does your work inform your activism around worker’s rights and vice versa?

I am fortunate in many ways. I am both Mexican and American. I have two passports and I can enter and exit both countries whenever I choose to. I have friends who are not so fortunate and who came to the U.S. because they could not find good jobs back home. I feel a responsibility to talk about issues of social justice in my books. I tried to talk about the dangers migrants face in Pancho Rabbit and the Coyote and about segregation in Separate Is Never Equal.

I am fortunate in many ways. I am both Mexican and American. I have two passports and I can enter and exit both countries whenever I choose to. I have friends who are not so fortunate and who came to the U.S. because they could not find good jobs back home. I feel a responsibility to talk about issues of social justice in my books. I tried to talk about the dangers migrants face in Pancho Rabbit and the Coyote and about segregation in Separate Is Never Equal.

My upcoming book, Undocumented, is based on my senior thesis. It is about my friend’s journey to the U.S. but also about his fight for better working conditions. There is a lot of animosity towards immigrants these days. Many people are quick to point out that undocumented immigrants break the law when they come into this country. But not many are willing to recognize the exploitation that the undocumented experience. Unauthorized immigrants work in some of the most grueling jobs like farming and construction. We often benefit from their hard labor, whether we recognize it or not. Hopefully the book will help people become more aware of that aspect of the immigration debate.

Do you think the children’s publishing industry has a diversity problem? If so, do you think that’s changed since you published your first book?

When I first started making picture books I was not aware of the lack of diversity in children’s books. Now that I have been in the field for about ten years I’ve become very aware of the issue. I try to make books where Latinx children can see themselves and their culture reflected. There is only a small number of those books available even though Latinx children are such a large part of the U.S. population. Hopefully my books will help Latinx children see that they matter and that their stories are important. I hope that non-Latinxs can connect with the books too and that it helps them see that we are all more alike then different regardless of our race, ethnicity, religion, sexual preference or physical abilities.

We Need Diverse Books has done a great job of speaking about the issue in recent years. I think publishers have been receptive to the call for diversity and some improvements have been made. But it is not enough. The amount of diverse books out there is still very small. I am hopeful that things will continue to improve. But I am also skeptical. I don’t want diversity to be something trendy that fizzles out quickly. I think we need to be vigilant and not get complacent. We can all do our share to foster more diversity, whether we are authors, illustrators, editors, reviewers, librarians, teachers, parents or readers.

What do you see the role of printed books playing, particularly for young and emerging readers?

Electronic books are convenient because they are readily available. They are cheaper and more ecological. But they feel distracting to me. I have a three-year-old daughter and an eight-month-old son. I always read them physical books, especially at bed time. I think printed books allow for a more focused experience. In our lives we are constantly in front of screens; whether it is computers, cell phones, or television. If I am reading for pleasure I don’t want to do it in front of a screen. When ebooks first came out some years ago I got the impression that publishers were worried about the future of the printed book. Now that ebooks have been around for a few years I don’t get that impression anymore. I don’t think the printed book is going away anytime soon. Certainly not in my house.

Electronic books are convenient because they are readily available. They are cheaper and more ecological. But they feel distracting to me. I have a three-year-old daughter and an eight-month-old son. I always read them physical books, especially at bed time. I think printed books allow for a more focused experience. In our lives we are constantly in front of screens; whether it is computers, cell phones, or television. If I am reading for pleasure I don’t want to do it in front of a screen. When ebooks first came out some years ago I got the impression that publishers were worried about the future of the printed book. Now that ebooks have been around for a few years I don’t get that impression anymore. I don’t think the printed book is going away anytime soon. Certainly not in my house.

Are there any projects that you’re working on now that we can follow?

My upcoming book Undocumented: A Worker’s Fight will be available on August 7th. I’m starting to work on a new picture book but it is in an early stage still.

How can people stay up to date on your work?

I’m on Twitter @duncantonatiuh and on Facebook at Facebook.com/DuncanToantiuhArte You can check out my website at DuncanToantiuh.com and my blog, too: duncantoantiuh.wordpress.com.

Community Spotlight is a blog series that seeks to connect people power with print power. Each post will feature a person or organization using print and design to do great work in their community and fight for a more just world. Subscribe today and let’s start building together.